What is an Inbox Simulation

On the surface an Inbox is an interactive fictional story that unfolds through email. Underneath the hood they are tests, tutorials, skill builders, living case studies, etc.

Participants love them. The player takes on the role of the main character in the story. They get emails from other characters. These emails can have attachments (docs, images, videos). Sometimes an instant message pops up instead of an email. As the story unfolds, emails present problems and ask for solutions.

Instead of writing a reply (which is an option), the player selects from a list of responses - say A, B, or C. If the player chooses A, the Inbox might:

- Trigger a future email a few minutes from now.

- Apply a point score to a skill that we are measuring.

- Select an “adaptive” future email, as in an adaptive test. Depending on the response, the player sees an easier or harder email in the future.

- Trigger an instant message from a boss.

- Trigger feedback about the response, either immediately in an instant message, or in a feedback report after completion.

The result is something like a text-based adventure game, where the player enters “a great underground empire” to explore a vast labyrinth of caves, solving puzzles and collecting treasures on their journey. Both text games and video games are successful because they put the player in the storyline where they can make decisions and experience their consequences. Inboxes do the same, but they have a practical purpose that goes beyond entertainment.

Put yourself in the participant's shoes. Would you prefer to be a part of the story, or take a passive role in a slide show, article, or video? Is it any wonder that participants love Inboxes?

Inboxes are ADA and GDPR compliant, and they are designed to collect “big data” across populations.

Inboxes are a type of simulation - they evolve based upon the user’s choices, and outcomes vary from player to player. They can trigger an emotional response in the player, and that anchors learning objectives in training applications.

They differ from business simulations in a few fundamental ways:

- Time scale - An Inbox’s time scale is real-time or close to it. A business simulation can stretch across simulated years.

- Real world - Inboxes can mimic the real world. Characters can represent real people. Scenarios can be inspired by actual events.

- Delivery time - an Inbox usually takes up 15 to 120 minutes. Business simulation deliveries range from a half day to months.

Use Cases

Inboxes are used as tests, tutorials, surveys, marketing instruments, living case studies, skill builders, assessment tools, and onboarding instruments.

Applications? Try to think of something that cannot be explored with email. Chopping wood? We could email you a list of axes, or a video on chopping technique. If humans can talk about it, they can employ email. Typical applications include:

- Leadership development training

- Recruiting new employees

- Customer service training

- Negotiation training

- Performance evaluation assessment

- New product training

- Course review

- Assessment for accreditation

Recruiting. Model the job in an Inbox. Ask candidates to play the Inbox to assess their skill levels. Populate it with real world characters and situations. Two things happen. Some candidates say thank you and leave, which saves everybody time. Some candidates become enthusiastic. In the interview talk about the situations presented in the Inbox. After hiring use the data collected for training and onboarding. One of our clients, a recruiting firm, told us that they cut their costs by half using Inboxes.

Seminars. Inboxes can be the vehicle for a seminar. Consider a seminar on the question, “When should a manager call the legal department?” Lecture for an hour on a topic, then break the class into teams of 4-6 participants. Ask the teams to do a short Inbox about the lecture. Consequences can include gained or lost sales, lawsuits, even jail, all in the spirit of good fun.

Pre-work. Obviously, an Inbox can serve as pre-work for a course or seminar. But here is an interesting twist. Why not use an Inbox as a marketing and survey vehicle to attract participants? Ask the target audience to do the Inbox. Present it as a fun exercise where people can discover their competency level at whatever the course is about. Prospects ask themselves, “Can I handle these situations or not?” If not, the solution is to take the course. As a side benefit, HR gathers data about the population’s competency level.

Post-work. Similar arguments apply to post-work. The interesting twist here is that seminars do not have to end. Periodic Inboxes can refresh important concepts.

Communications. Why not highlight important stories from the past month in an Inbox? Put people in the same critical situations that their peers faced and ask, "What would you have done in this situation?" The Inbox both alerts the audience to a real-life issue and prepares them to offer an appropriate response.

Continuous learning. Use Inboxes as a subscription service. Once each month, send subscribers this month’s Inbox. As attachments, the emails can offer videos, images, and documents. The subscription keeps people sharp by putting them into unusual but high consequence situations. Compare this with flight simulators, where pilots encounter black swan events. Better to face them in an Inbox before they come up in real life.

Assurance of Learning. Accrediting bodies like the AACSB have a quality control requirement called "assurance of learning". Inboxes can collect high quality data effortlessly.

- Write a "course review" Inbox that assesses student understanding of the course material. The Inbox is structured as an adaptive, drill-down test that precisely measures the course's learning objectives.

- Required it as a pass-fail take-home assignment just before the final exam.

- Tell students, "This Inbox reviews the course. It is better than Cliff Notes. It diagnoses your strengths and weaknesses. It will tell you exactly what you need to study before the final exam. It reviews all of the course topics. It even gives you feedback to correct bad answers. It is pass-fail. If you complete it, you pass, regardless of how well you do. We also use it as a quality control instrument to improve the course."

- Students will not cheat. The Inbox saves them time by identifying what they already know, allowing them to focus upon their weaknesses.

- It lowers the instructor's workload. No class time. No course review. No grading.

- The school gets comprehensive data specific to the course that can cut across sections, campuses, programs, instructors, and semesters.

Student Feedback

An Inbox is a simulation, an interactive story. Often the designer can build feedback directly into the storyline. For example, the user selects a good answer, and a few minutes later an instant message pops up that reads, “Great news! They accepted our offer!” And a few minutes after that, “Uh-oh. The warehouse just burned down.”

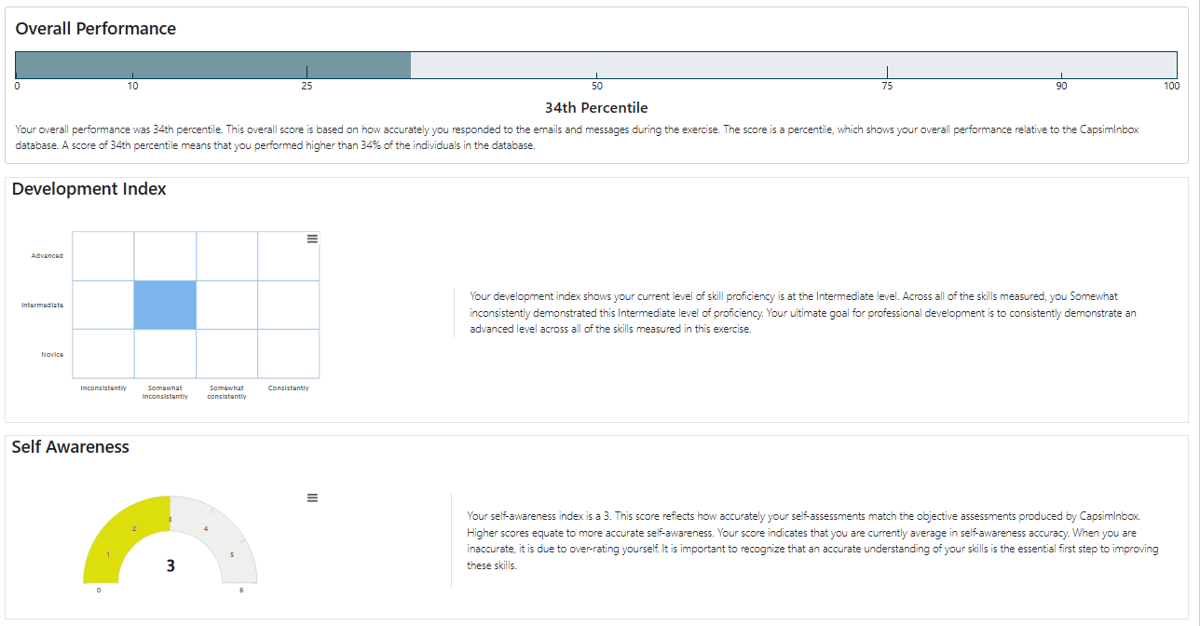

In most Inboxes, users want to know how well they did, how they compare with their peers, and what they can do to improve their skill levels.

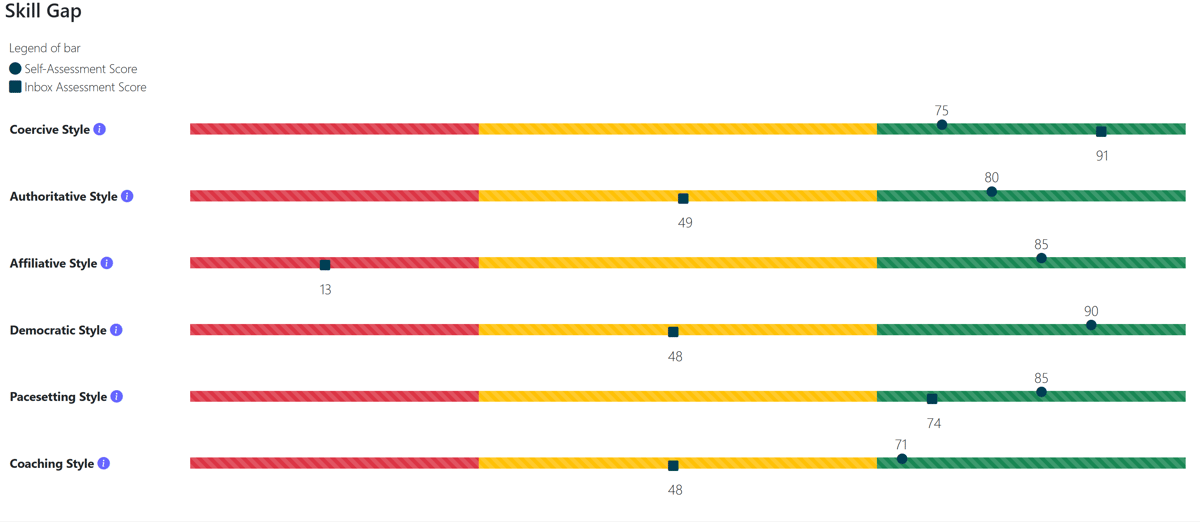

All Inboxes are built around a set of skills (learning objectives) which are measured by the responses. The reports pictured below were drawn from a “Leadership Styles” Inbox that was delivered to a class of MBA students.

The Inbox asked, “Can you identify the leadership styles of people?” At the beginning of the Inbox students were asked, “Relative to 100 peers, where would you rank yourself in your ability to recognize each of the following leadership styles?”

- Coercive style

- Authoritative style

- Affiliative style

- Democratic style

- Pacesetting style

- Coaching style

Students took the self-assessment before the Inbox began to clarify the skills in in their minds and boost their interest level. At the end of the Inbox students compared their expectations against results. For example, this student expected to score 85 on Affiliative Style but actually scored 13.

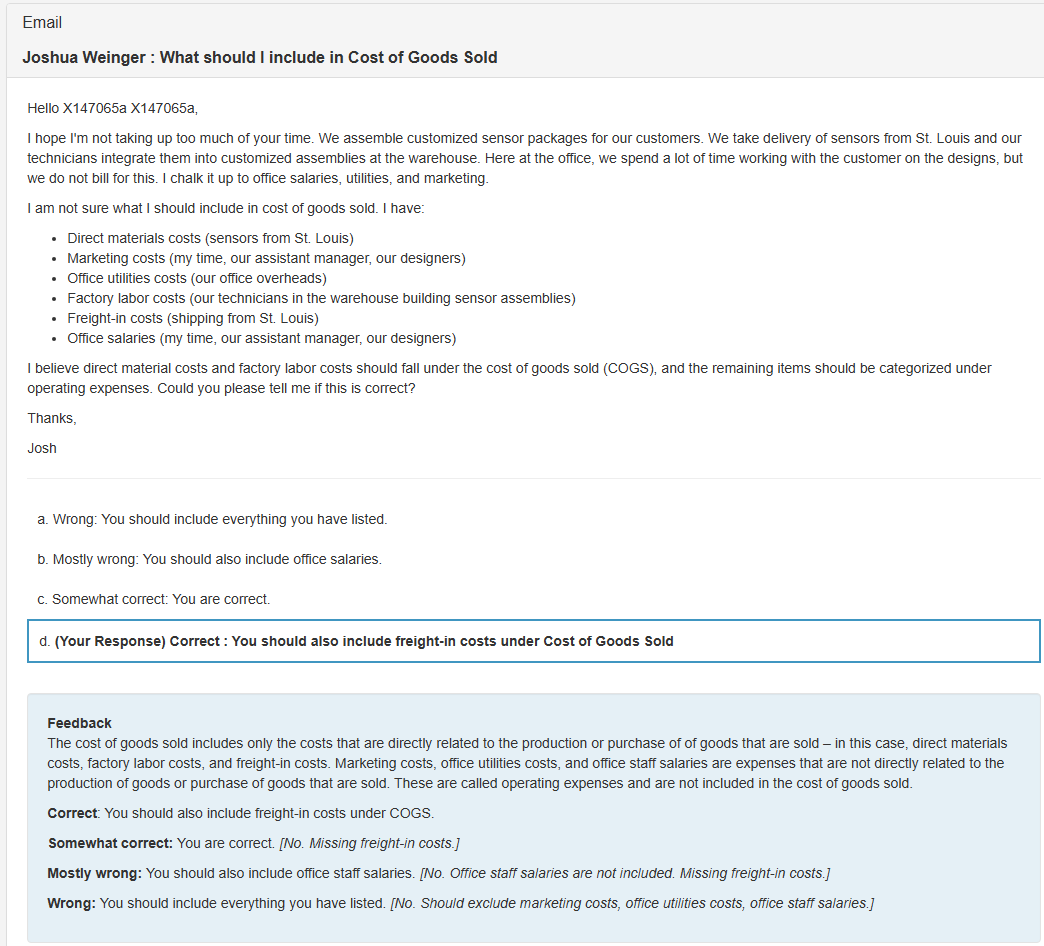

Designers can also write a detailed feedback report for each email. The example below is extracted from a business school accounting class. The Inbox is used as a pass/fail course review, and it also collects data for an accreditation requirement called “Assurance of Learning”.

Instructor/Administrator Feedback

Instructors want to know how their students did, and administrators how their population did. Inbox reports can serve both.

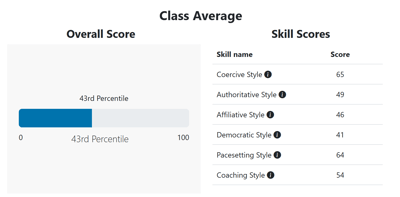

Class Average Report. Here we have results for an MBA class taking the Leadership Styles Inbox. Relative to the population, the class scored at the 43rd percentile.

Class Average Report. Here we have results for an MBA class taking the Leadership Styles Inbox. Relative to the population, the class scored at the 43rd percentile.

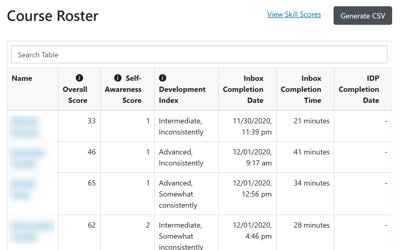

Course Roster Report. Besides names and overall scores, the instructor can look at behavior. When did students do the Inbox, how long did they take, how much further development do they require?

Course Roster Report. Besides names and overall scores, the instructor can look at behavior. When did students do the Inbox, how long did they take, how much further development do they require?

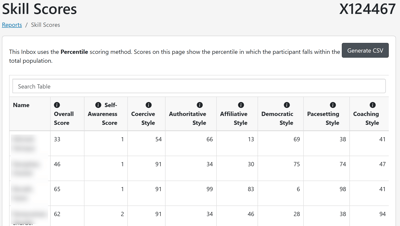

Skill Scores by Student. How did students do on each skill?

Skill Scores by Student. How did students do on each skill?

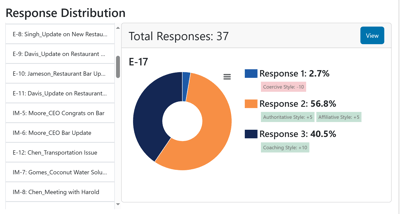

Response distribution. Are any of the emails suggesting conceptual trouble? Perhaps the instructor should clarify the distinctions when they are introduced. Designers are also keenly interested in this report. Here we have an email where almost as many students chose Response 3 as Response 2. Ideally we would see one response do clearly well, and the remainder split what is left evenly.

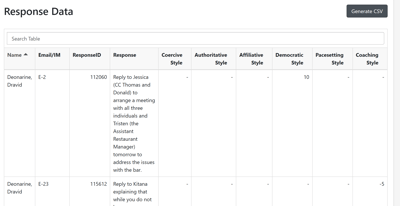

Response distribution. Are any of the emails suggesting conceptual trouble? Perhaps the instructor should clarify the distinctions when they are introduced. Designers are also keenly interested in this report. Here we have an email where almost as many students chose Response 3 as Response 2. Ideally we would see one response do clearly well, and the remainder split what is left evenly.  Response Data. This report lists each student’s responses and their point score. It is the fine detail report.

Response Data. This report lists each student’s responses and their point score. It is the fine detail report.

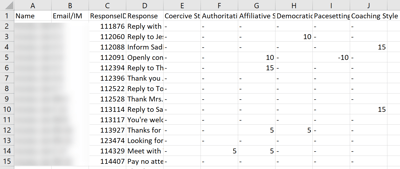

CSV files. Of course, all data is easily downloaded as a CSV file for further analysis.

CSV files. Of course, all data is easily downloaded as a CSV file for further analysis.

Big Data

Inboxes collect data. How can we organize this data into meaningful reports for big organizations?

Without getting too technical, reports are built up from an email’s score. From this basic nugget of information, we can build reports for:

- An end-user.

- A small population - class, seminar, applicant pool, a demographic group, etc.

- A large population - a school or division, a corporation, the entire population of end-users.

- A skill - across Inboxes, populations, or time.

Inbox Authoring Platform

Instructional designers use the Inbox Authoring Platform to create Inboxes, in much the same way that they use Microsoft’s PowerPoint to create slideshows or Excel to create spreadsheets. Inbox developers:

Instructional designers use the Inbox Authoring Platform to create Inboxes, in much the same way that they use Microsoft’s PowerPoint to create slideshows or Excel to create spreadsheets. Inbox developers:

- Create Inboxes for users inside their organization.

- Sell Inbox development projects to their clients.

- Publish and sell finished Inboxes to customers.

Designers can learn how to write an Inbox in a few hours. Writing Inboxes is easy, especially with the help of modern AI's.

- Train designers for free. Just contact us to set up a designer's account.

- Write Inboxes for free. Designers can write, edit, and test their Inboxes at no cost to them.

You own the Inboxes you create - the copyrights are yours.

Often our clients want Capsim to produce their first Inbox. No problem. We can show you the ropes. We can also offer you independent designers to help you with your project.