Five Ways To Shape Ethical Decisions: Rights Approach

May 17, 2018

Last time, we talked about the Utilitarian Approach to ethical decision-making. More generally, we are reviewing five theories that provide the ethical building blocks you can use in your classroom to debrief any ethical dilemma. Of course, every dilemma can be dissected using more than one approach, and thus, the end result or decision may be different depending on the road taken.

The Rights Approach focuses on respect for human dignity. This approach holds that our dignity is based on our ability to choose freely how we live our lives, and that we have a moral right to respect for our choices as free, equal, and rational people, and a moral duty to respect others in the same way.

Some of these rights are articulated in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights such as: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; free speech and assembly; freedom of religion; property ownership; and to freely enter into contractual agreements and the right to receive whatever was contractually agreed. Other rights might include the right to privacy, to be informed truthfully on matters that affect our choices and to be safe from harm and injury, etc. A deeper understanding of human rights can be gained from the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

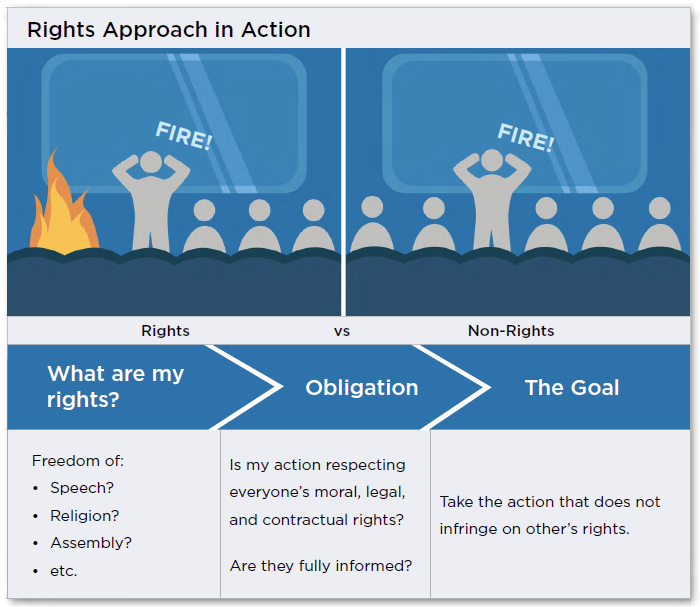

This approach asks us to identify the legitimate rights of ourselves and others, in a given situation, as well as our duties and obligations. Consider how well the moral, legal, and contractual rights of everyone are respected and/or protected by the action, and assess how well those affected are treated as fully informed, sentient beings with the right to free consent instead of just as a means to an end. As such, the ethical action would be the one we have a moral obligation to perform that does not infringe on the rights of others.

When confronted with conflicting or competing interests or rights, we need to decide which interest has greater merit and give priority to the right that best protects or ensures that interest. For example, in the United States, the right to freedom of speech is generally protected, but citizens do not have the right to needlessly scream “Fire!” in a crowded theater or to engage in hate crimes. We may also want to ask whether we would want to be on the receiving end of an action if the situation was reversed, or what the impact would be if everyone performed an action.

.png?width=80&name=1-questions%20(1).png)